5 reinvention rules that saved 3M from bankruptcy

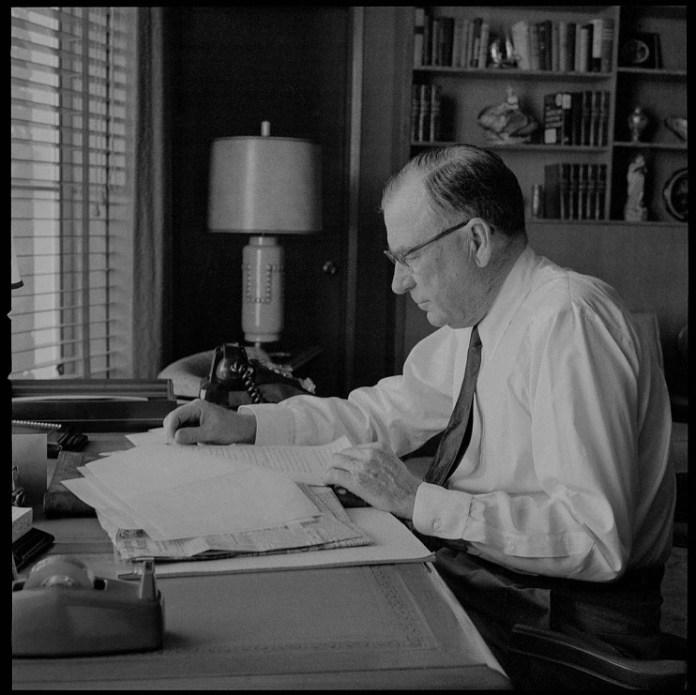

“If you put fences around people, you get sheep. Give people the room they need.” — WILLIAM L. MCKNIGHT

3M is one of the world’s most innovative companies, having generated more than 100,000 patents since its 1902 founding.

But in 1904, the company — then known as the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company — was failing. Although the company’s five founders had invested time, money and hard work into the business, their first sale of the mineral corundum ended up being their last. Three years would pass before the founders discovered their mistake: Their mines did not contain corundum. They contained anorthosite, a commercially worthless mineral. By November 1904, the company had no funds to continue operations and faced mounting debt.

How, then, did the founders turn the company into what 3M is today? Their story reveals that it took a combination of innovation, curiosity, resilience and grit. Or, framed differently, it took these five rules.

Rule 1: Never give up on ideas that you believe in.

To save 3M, the founders agreed to sell controlling interest to raise cash. But who would invest in this struggling enterprise?

In January 1905, 3M shareholder Edgar Ober paused over breakfast as he read a letter from his friend and 3M founder John Dwan outlining the company’s dire situation. Ober believed the company should abandon mining and start manufacturing abrasives. It would take $14,000 to settle debts and another $25,000 to start a factory. Ober was prepared to invest beyond his initial $5,000 outlay but needed a partner. He met that morning with businessman Lucius Ordway, persuading him to invest. Ordway had one caveat: He wanted “nothing to do with running the company.”

Ober’s March letter to Dwan outlined terms for purchasing controlling interest. At the May 1905 annual meeting, Ober was named 3M’s new president. Apart from one three-year break, Ober served as president until 1929 — the first 11 years without compensation.

In January 1906, sandpaper orders dribbled in, but expenses outpaced sales. By November, Ordway had invested $200,000. There was no quit in 3M.

Rule 2: Allow your people to reimagine what’s possible.

To outsiders, 3M was the “largest sandpaper company in the world,” but the enterprise was struggling.

When William McKnight applied for a job as assistant bookkeeper, he was so nervous his handwriting was illegible. The company turned him down. But on May 13, 1907, McKnight interviewed again and was hired for $11.55 a week. He would succeed Ober as 3M’s president.

McKnight was observant, hardworking and loyal. He was named the company’s first cost accountant in 1909. By putting two and two together, he realized 3M needed help selling products, cutting costs and improving product quality. McKnight attacked these problems with intelligence and energy. In 1911, he was named office manager of 3M’s nascent Chicago office.

McKnight brought an obsession with quality and a disdain for discounting — philosophies that ultimately ensured both his and the company’s future. He believed 3M should avoid highly competitive markets. In 1914, McKnight became 3M’s general manager, distinguishing himself by developing product improvement processes and sticking to his principles during a five-year price war when competitors were “standing by, waiting for 3M to fail.” In 1915, McKnight was elected vice president. He was 29-years-old.

Ober became McKnight’s friend, mentor and adviser. Through savvy decision-making by both men, 3M was debt-free by 1916. McKnight was 3M’s missing ingredient. From the time he became general manager in 1914 until his 1966 retirement, 3M’s sales increased by 17.1 percent on a compound annual growth rate basis — from $264,000 to $1.2 billion.

Rule 3: Take risks when you see opportunity.

William McKnight opened a letter one frosty day in January 1920 that would change the course of 3M’s history.

It was from Francis Okie, who requested “samples of every mineral grit size you use in manufacturing sandpaper.” McKnight could’ve replied that 3M wasn’t in the business of selling bulk minerals. He could’ve ignored Okie’s letter. Instead, the letter triggered his curiosity.

Okie had invented waterproof sandpaper. But his investors lost interest when he couldn’t obtain materials. Okie wrote to 3M and said that he wanted to buy “enough to get started.” Learning of Okie’s invention, McKnight initiated an 11-month courtship culminating with Okie selling 3M the rights — and making 3M the global leader of abrasives.

Rule 4: Encourage curiosity and exploration.

McKnight valued the power of curiosity. He believed that sales weren’t created by leaving brochures with receptionists, but by talking with shop-floor workers to learn what problems they encountered with competitive products. McKnight also drove collaboration between 3M’s salesmen and its factory.

By 1925, 3M’s policy manual warned, “No plant can rest on its laurels — it either develops and improves or loses ground.” In 1948, McKnight created a rule that encouraged 3M technical employees to devote up to 15% of their working hours to independent projects.

Before McKnight codified curiosity as a foundational value, inquisitiveness sparked the 1925 invention of masking tape and, in 1929, Scotch tape. McKnight also stipulated that 30% of 3M’s revenues must come from products invented within the past five years.

Rule 5: Embrace failure as part of the innovation process.

By giving employees the freedom to spend nearly one full day each week daydreaming, 3M generated billions of dollars. “The mistakes that people will make,” said McKnight, “are of much less importance than the mistake that management makes if it tells them exactly what to do.”

Vistage Member Exclusive Event – 3M Innovation Center Tour

So how did a small-scale mining venture in Northern Minnesota grow into a global powerhouse? On Monday, June 24, go behind the scenes to see firsthand the innovation and perseverance so ingrained in company culture, it has endured more than 100 years — propelling 3M from humble beginnings to Fortune 500.

With Vistage member and 3M’s Technical Director of Corporate Research Process Laboratory, Dr. Philip G. Clark as your guide, learn how the spirit of innovation and collaboration continues to drive 3M researchers and scientists today.

Space is limited. Register now for this members-only event.

3M Innovation Center in St. Paul, Minnesota

Monday, June 24, 2019

7:30 a.m. – 10:00 a.m.

Related content

5 leadership lessons from FDR that inspire reinvention during times of change

This article is an edited excerpt from How Leaders Decide: A Timeless Guide to Making Tough Choices, the No. 1 new historical reference book on Amazon.

Category: Innovation

Tags: Innovation, Leadership, reinvention